A £350m contract to provide water and wastewater to Scotland’s public sector has been awarded to a privatised utility firm in East Anglia. Confused?

Scotland has a public water corporation, Scottish Water that is accountable to Scottish Ministers and the Scottish Parliament. Scottish Water is responsible for the provision of water and waste water services to almost all domestic and non-domestic properties and for maintaining the public system.

However, there is competition in the provision of customer-facing activities such as billing, charge collection, meter-reading and complaints handling for non-domestic customers in Scotland. This means that Scottish Water levies a wholesale charge on licensed retailers for non-domestic customers. Licensed retailers can agree their own charges with customers, subject to them being no higher than a default tariff set by the Water Industry Commission Scotland (WICS). Scottish Water is also a retailer; through its own retail arm Business Stream, which provides a service to the vast majority of non-domestic customers in Scotland.

The market was created by the Water Services etc. (Scotland) Act 2005. The then Labour led administration was persuaded that this was the least they could get away with due to the provisions of the UK Competition Act 1998. The 2005 Act prohibited common carriage and household competition and put a licensing regime in place for non-domestic competition. UNISON Scotland opposed the legislation and would argue that it has simply created an unnecessary bureaucracy. The claimed savings are almost entirely down to water efficiency measures that do not require competition to implement.

As the public bodies are non-domestic customers they come under this system of retail competition and the Scottish Government, actually the then Infrastructure Secretary Nicola Sturgeon, put one big contract for public bodies out to tender last August. It could be argued that this was not the best way to organise this tender.

It appears that Anglian Water has submitted the lowest price bid in an evaluation that was 50/50 price and quality. The Scottish Government is not obliged to accept the lowest bid, but it would have to have a good reason for not doing so under the utilities procurement regulations. In fairness, the Scottish Government had few options because the system of retail water competition is the ultimate in market madness. £350m will be paid to Anglian Water in Huntingdon, only for most of that money to be repaid to Scottish Water in wholesale charges. The cost of this crazy system is picked up by the taxpayer. However, it was unwise to include savings from water efficiency measures that should be undertaken anyway to spin out the alleged benefits of the contract.

It would also be interesting to know if the evaluation panel took into consideration the risk that this bid was a loss leader to give Anglian Water a base in Scotland. This is important because contractors who do this squeeze a margin post-contract from quality.

The direct job implications are not likely to be huge, but significant for those impacted. Competition only covers the customer facing services i.e. call centre, customer service and transactional staff within Business Stream.

This procurement also highlights the importance of addressing tax dodging in procurement, an issue UNISON and other civil society organisations campaigned for during the passage of the Procurement Act. There should be pre-qualification disclosure of company taxation policies and public bodies should be able to evaluate a tender on the basis of which company pays tax or not. Assessment of bids could make use of the Fair Tax Mark.

The significance with this contract is that Anglian is one of a number of private water companies who are happy to take taxpayer funded public contracts, but less happy to pay corporation tax. A consortium called Osprey, made up of asset and pension managers in Canada and Australia, owns Anglian Water. Corporate Watch reported that Anglian paid £151 million to its private owners, but just £1 million in tax in 2012, after an operating profit of £363 million. It avoids millions in tax by routing profits through tax havens by way of taking on high-interest loans from their owners through the Channel Islands stock exchange.

Anglian Water was described as a “significant repeat offender” in an Environment Agency report on polluters and was fined for polluting five years in a row. Friends of the Earth said of the company: “Clearly, this company is a classic example of a company which sees pollution fines as a legitimate business expense and doesn't care about the environment”. It would be interesting to know just how much weight the evaluation panel gave to this in their quality weighting.

Non-domestic competition is not the only area of privatisation within Scottish Water. Last year the insider web site Utilities Scotland submitted FoI requests to ascertain the extent of privatisation in the delivery of the water and waste water capital programme. In the last four years, 92.5% of Scottish Water’s capital programme has been delivered by private contractors, 7.5% by Scottish Water staff. By any standard that is substantial privatisation. This is on top of PFI schemes run by a variety of privatised water companies.

We are also concerned about the impact the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) could have for Scotland’s public service model. The greater the privatisation, the easier it will be for overseas corporate interests to challenge our public water system.

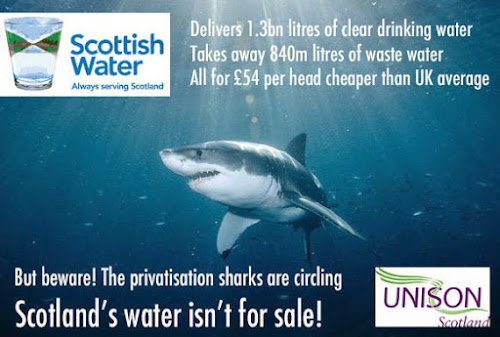

Scottish Water works well, is good value for money and water customers support the corporation staying in the public sector. While there were limited options for the Scottish Government on this occasion, we should be aware of the pressures for privatisation and the lessons to be learned for future procurement.