The importance of social capital and involving people in decisions making have been highlighted as key issues in explaining why people living in cities like Liverpool and Manchester have much better health than those living in Glasgow. These cities, like Glasgow, have been through deindustrialisation and experience similar levels of poverty and inequality yet Glasgow has 30% excess for premature mortality and 15% excess for deaths of all ages.

The latest report from Glasgow Centre for Population Health: History, Politics and Vulnerability in Scotland and Glasgow is an important piece of work and anyone one looking at public sector reform in Scotland should be studying it in detail in order to avoid repeating the mistakes of the past.

Key features of Scotland’s health problems

Excess mortality compared with the rest of the UK

• is seen all over Scotland but it is greatest in the West of Scotland and in particular Glasgow

• It is increasing

• It exists across all social classes

• It exists for a broad range of causes of death but key issues for premature mortality are death from alcohol, drugs and suicide and for excess death at all ages from cancer, heart disease and stroke.

The figures are startling: In 2011-12 the “excess death for alcohol related disease was 2.3 times higher for Glasgow than for Liverpool and Manchester and 70% higher for suicide.

It has been clear for some time that poverty and inequality impact on health outcomes but the problems in Scotland and Glasgow in particular are more complex. The differences in poverty and deprivation no longer explain the mortality gap between Scotland and the rest of Britain. In other cities like Liverpool and Manchester where the population has and is experiencing poverty, inequality and deindustrialisation (and are at the wrong end of England’s health outcomes tables) people do not have health outcomes similar to Glasgow and Scotland.

The report’s finding indicate that Scotland’s population and Glasgow’s in particular have been “made more vulnerable” to the impact of poverty, inequality and deindustrialisation.

Key issues

• Lagged effect of historical levels of deprivation: Glasgow has had notably higher levels of overcrowding from at least the middle of the twentieth century

• Impact of the New Town programme: these programmes relocated younger skilled workers and their families and encouraged growth of “modern lighter industries” away from Glasgow. The policy focus was therefore not on investing in Glasgow but in getting people out of it.

• Glasgow undertook substantially large slum clearances and building demolitions with a greater emphasis on creating within city peripheral social housing estates, more high rise development and much lower per capita investment in housing repairs

• Moving on to the 1980s: Glasgow prioritised inner city gentrification and commercial development whereas Manchester and Liverpool reacted to cuts differently. In particular the city level response in Liverpool was one of building participatory models of development leading to a focus on building new council houses and public amenities.

• The report found high levels of social capital (strong community ties) in Liverpool

• The team speculate that Manchester’s greater levels of ethnic diversity may also have been helped them withstand the effect of poverty and deprivation.

Implications for policy

The key point the report emphasises is that economic policies “matter for population health” and that if we are to improve Scotland’s health then we need to address three issues simultaneously

People need to be protected from poverty and deprivation

Work needs to be done to address the existing problems and mitigate against future vulnerabilities caused by the cuts to public services particularly though not exclusively social security.

Importantly Scotland while mitigating the impact is important reduce the inequalities in income and wealth are essential to narrowing health inequalities within Scotland.

Recommendations are grouped under four headings and detailed examples are included in the report.

Scottish Economic and social policy

The report urges all opportunities are taken to redistribute income and wealth across Scotland: including measures relating to ownership of capital, income and corporate taxation, wealth and asset taxation, and fair work.

Housing and physical environment

Examples include expanding the social house building programme and extending the Scottish Housing Quality Standard

Targeting cold and damp housing

Local government actions

Local government is encouraged to recognise impact of local decision making on population health. The report emphasises the role of local government plays in redistributing resources towards areas of greater need and so questions are raised about whether to review boundaries and/or the funding allocation for local government. A poverty proofing approach to local government policy making is also recommended

Understanding deprivation

As ever they call for further research on the nature and experience of deprivation in Scotland

This is an extensive and important piece of work which should inform the process of public sector reform in Scotland. The finding indicates the value of community involvement in developing their own solutions. This means also challenging the role of “experts” making plans on what they think is best. This of course can be a challenge to and for policy makers, politicians and of course professional advisers on policy.

Public services in Scotland are reorganising and refocusing in response to both budget cuts and changing demands. We can’t afford to keep getting it wrong, as this report shows lives are at stake.

Public Works is UNISON Scotland's campaign for jobs, services, fair taxation and the Living Wage. This blog will provide news and analysis on the delivery of public services in Scotland. We welcome comments and if you would like to contribute to this blog, please contact Kay Sillars k.sillars@unison.co.uk - For other information on what's happening in UNISON Scotland please visit our website.

Wednesday 25 May 2016

Tuesday 24 May 2016

Prospects for education services in Scotland

Giving the Deputy First Minister responsibility for education is meant to send a message that this service is a priority for the new government. So what might we expect in the coming years?

Let's start at the beginning, with early years. The SNP manifesto commitment is:

"By 2021, we will almost double the availability of free early learning and childcare to 30 hours a week for all 3 and 4 year olds and vulnerable 2 year olds – a policy that will save families over £3,000 per child per year. To deliver this expansion, we will invest an additional £500 million a year by 2021 and create 600 new early learning and childcare centres, with 20,000 more qualified staff."

By any standards this is a big and welcome commitment, even over a five year period. The first delivery challenge is budgetary. Is £500m really enough to pay for 600 new centres and 20,000 staff? By my calculations this will barely cover the cost of employing qualified staff at todays pay rates. Then you have the capital and revenue costs of the new buildings, which is difficult to calculate, but will be huge. Perhaps it's a good thing the former finance cabinet secretary is now running education - he will need to do the 'loaves and fishes' miracle with this one!

What the manifesto doesn't say is how and who will be delivering this massive expansion. As the UNISON Scotland early years manifesto sets out, this is best delivered as a public service with fairly paid staff. Working with children is not just about the time spent with each child. Workers also have to plan, evaluate, and assess learning and keep detailed records of each child’s progress. There needs to be wider recognition of what these posts involve and adequate funding for the staffing levels and hours of work required to do the job.

Schools and closing the attainment gap is the next challenge. There has been some ridicule from opposition parties over John Swinney’s call for some time, given they have been in power for nine years. However, he does at least bring a fresh pair of eyes to the challenge and as UNISON has pointed out in our submission on the Education Bill, the attainment gap is rooted in our unequal society, not simply what happens in schools.

The specific proposals in the SNP manifesto have a very Tory/New Labour feel about them - testing, targets, and funding directly to schools bypassing local authorities. Sadly, there is little evidence that these approaches have worked elsewhere and it is noticeable that the advocates of academies and free schools in England are now calling for larger groupings of schools, as large as 25 schools. That looks remarkably like a local educational authority to me!

What is sensible is the plan to renew the focus on literacy, numeracy, health and well-being – targeting support on areas with significant areas of deprivation. Investing £750m ‘in the next parliament’ in the Attainment Fund and £100m from the Council Tax changes will be welcome - even if the extra bureaucracy of head teachers having to administer it isn’t. There is also a welcome recognition that teacher numbers are not the only solution – classroom assistants get a mention after years of cuts. School libraries also deserve greater recognition.

The biggest structural change is the proposal to create ‘new educational regions to decentralise management and support’. That sounds like tautology to me, but we can only assume it means regionalising education authorities, while allocating more resources directly to schools. This will be backed up by ‘more focused and frequent’ school inspections.

The next stage in the education journey is colleges. After years of cuts, regionalisation and 2000 job losses; the commitment is to, ‘maintain the number of full-time equivalent college places that lead to employment’. There is an understandable view in the sector that they have paid the price for extra university funding. However, there should at least be a bit of stability going forward.

For universities the focus is on improving access for students from the most deprived backgrounds. Free tuition is the right policy and enjoys cross party support, but it has done little to improve access. They will adopt the recommendations of the Widening Access Commission and set a new target of 20 per cent of students entering university to be from Scotland’s 20 per cent most deprived backgrounds by 2030. Reviewing bursary support for students in colleges and universities will be an important part of achieving that target.

It is pretty clear that the new government’s education focus is on early years and schools. Educational inequality starts young, certainly before school age, so that is the right priority. The row over the Named Person scheme is frankly a distraction from more important issues. The big challenges will be financial, particularly in early years where the ambition doesn’t match the budget. In schools there will be significant scepticism that the outlined structural reform will contribute to the solutions, but targeting additional funds where it is most needed, is the right approach.

Tuesday 17 May 2016

The prospects for NHS Scotland and health policy

Improving the health of people living in Scotland ought to be a high priority for any government – so what might we expect from the next Scottish Parliament session?

Health inequalities remain Scotland’s most enduring problem as this week's GCHP report shows yet again. Life expectancy between the wealthiest and poorest areas remains stubbornly high. The SNP manifesto included a brief mention of health inequalities and that in the context of public health, with the promise of a new strategy on diet and obesity. Of much greater significance will be commitments to new housing and income support through devolved welfare powers. However, these measures will be constrained by the impact of austerity on public spending in Scotland and the limited use of new taxation powers.

One of the few SNP manifesto spending commitments is an increase in the NHS revenue budget by £500m ‘by the end of this parliament’. This is a modest increase over five years that should be funded from the Barnett consequential of English NHS spending.

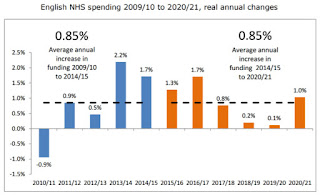

As we will be relying on these Barnett consequentials, we should take a closer interest in what is happening south of the border. Professor Andrew Street at the University of York points out that the claimed £8.4bn increase in English spending by 2020-21 is actually closer to £4.5bn. The chart below shows how this spending might be increased each year and the average 0.8% looks very low. The modest £500m increase promised for NHS Scotland therefore looks like John Swinney’s pragmatic assessment of the Barnet consequentials.

NHS England has highlighted a £30bn spending gap by 2020/21, of which the UK government claims to be providing £8bn. Wage and drug costs; a growing and ageing population; and a trend in activity demand, over and above the demographics, explains the gap. There are similar pressures in Scotland. Even if our population growth is slower than England, we have an older population and poorer health that drives up costs. NHS England’s ‘Five Year Forward View’ has some pretty optimistic solutions, including ‘a radical upgrade in prevention and public health’ and a shift to primary care.

It is not even clear that the Barnett consequentials will reach actual health board budgets, which are already under pressure. The SNP manifesto unhelpfully compounds the annual increase and claims it totals £2bn over the parliament. However, they are also committed to investing £1.3bn ‘from the NHS to integrated partnerships to build up social care capacity’. It is unclear if that is over and above the NHS revenue increase. It wasn’t in this year’s budget and it is hard to see where else this money is going to come from.

As councils deliver social care, this is a big dent in the NHS spend, although few would dispute the priority given to social care that is in a state of crisis and the need to end the waste in bed blocking. It will also help pay for the commitment to pay the living wage - an important first step in improving the recruitment and retention of staff in the sector.

There are some other specific spending commitments. £150m has been identified for mental health services. This is welcome and there were similar commitments in all the party manifestos; demonstrating that the underfunding of these services, particularly for children, has attracted everyone’s attention. There is also £200m for five elective treatment services, although the adequacy of that budget has been questioned and it is a suspiciously round number!

The number of staff working for NHS Scotland recovered to its pre-crash levels last year and is likely to grow again. There is a commitment to an extra 500 health visitors, training for an additional 500 advanced nurse practitioners, 250 Community Link Workers and 1000 paramedics ‘working in the community’. There will be another 100 GP training places and £23m to increase the number of medical school places. Extra staff on the establishment will be welcome, but given the number of vacancies at present, it may be some time before actual bodies appear on the ground.

As in England, the Scottish Government is looking to reform to plug at least some of the financial gap. The SNP manifesto says “The number, structure and regulation of health boards – and their relationships with local councils – will be reviewed, with a view to reducing unnecessary backroom duplication and removing structural impediments to better care”.

Reducing the number of health boards is a practical proposition when it comes to acute services and could be built around three or four major trauma centres. It is much more challenging when it comes to community services.

It is here that much will be expected from the new Integrated Joint Boards and it remains to be seen if these will continue as joint boards or morph into stand alone bodies. That will probably depend on how successful they are. Another option, as happens in other parts of Europe, is to move these services into local government. That option is unlikely in Scotland given the Scottish Government’s antipathy towards councils. The next GP contract could also be an opportunity to reform the antiquated small-business model, into something that is more integrated into the NHS or the IJBs.

What seems clear, is that the additional NHS staff and investment in social care are primarily focused on achieving what the SNP manifesto describes as “ensuring that our NHS develops as a Community Health Service”. Few would argue with that priority, as shifting resources from acute to primary care makes absolute sense. However, it has been an objective of many different governments over the years, in less challenging financial circumstances.

This is of course a minority government, but despite regular squabbling in parliament, there is a large degree of political consensus over health. Even the Tories are not immune from that consensus with little evidence of the market ideology that drives their counterparts in England. Labour and the Greens both put greater emphasis on tackling health inequalities and that also requires a shift from acute to preventative primary care services. If there is a difference in approach, it is structural - the opposition parties have a common preference for localism over centralisation.

On this basis, there appears to be a common understanding of the problems. The challenge remains to deliver the solutions in the context of austerity.

Saturday 14 May 2016

Changing public services

Public service reform could be one of the defining issues of the coming Scottish Parliament session.

I was speaking at the 'Leading Change in Public Services' conference at Queen Margaret University in Edinburgh today. An international gathering of academics and practitioners on this issue. There is some very interesting academic work being done on this issue across Europe that should inform our debate. My task was to set the scene by outlining public service reform so far in Scotland, likely new directions and some alternative approaches.

The challenges is the easy bit to describe. Public services are being savaged by austerity economics, and in Scotland, has largely been dumped on local government services. The chart below demonstrates this in financial terms.

The workforce numbers show this even more dramatically. A staggering 87% of the public sector job losses in Scotland since the crash have been in local government.

Job losses and finance are the biggest challenges, but not the only ones. We also have demographic change that is increasing demand on council services, particularly social care. Poor economic performance is also increasing demand as is the need for public services to respond to climate change. However, underpinning all this is Scotland's deep seated inequalities. As the Christie Commission highlighted five years ago, failure demand accounts for around 40% of public spending in Scotland.

The financial pressures are likely to get worse. There is about another £1.5bn of revenue cuts to come for Scotland in the current UK spending plans. The Scottish Government is not planning to use many of the new powers to take Scotland in a different direction to austerity. The tweaks to the higher rate tax bands and the Council Tax will mitigate the cuts by around £350m less £60m cost of cutting APD, unless as I hope, the opposition parties combine to stop this. Given the NHS spending commitments, it seems pretty clear that local government (less perhaps education) will continue to bear the brunt of cuts.

Apart from job losses, the impact on the workforce can be seen in UNISON Scotland's monthly 'Damage Series' of reports. Almost all staff groups comment on the salami slicing of services, the juggling of plates to the extent that many of them are now crashing. Just doing the statutory minimum, and often not even that, while abandoning much of the preventative work that they value and is so important if we are to tackle long term problems. It shows up in sickness absence, particularly stress and violence, and in a demoralised workforce with declining morale. We should also pay more attention to the ageing workforce and the lack of young people coming into public service.

Five years ago I was working on the Christie Commission report. It called for services to be designed from the bottom up with greater user involvement. The report argued for preventative spending and a focus on outcomes. It also called for more integrated working, breaking down the silos and even going as far as looking at the 'one public sector worker' concept.

While almost everyone agreed with the principles set out in the report, delivery has been mixed, as I set out in an article last year. While the essential Scottish public service model remains intact, we have greater centralisation, ministerial direction and a new approach of quangos directing policy, even when delivery remains local. In my experience, the longer ministers are in office, the stronger the temptation is to direct services from the centre, reinforced by the civil service culture.

The SNP manifesto points to a programme for the new government that envisages significant structural change. Reviews are promised of the structure of health boards and councils. New regional education bodies with more finance going directly to schools. There are also proposals to allow community councils to run some services and 1% of council budgets devoted to community budgeting.

This could lead to fewer health boards, which might work for acute services, but not for primary care. Of course they are subject to the new integrated joint boards with social care. If this form of joint working doesn't deliver greater joined up working, then the pressure to make them formal structures and the employer of staff will grow.

With education and social work going elsewhere, leisure and housing has already largely gone arms length, you are left with rump local authorities. They could be left to wither on the vine or merged, with decentralisation schemes that give communities a larger say in how the few services that remain are delivered.

Structural change is notoriously difficult and expensive. Organisations go into limbo while preparing for it and then spend years sorting out the new bodies. In the current financial climate it could be argued that is simply analogous to shifting the deck chairs on the Titanic.

At today's conference I didn't offer a prescription for a different approach, but I did suggest some principles that we might consider in the debate to come.

First and foremost, we should not simply roll over and accept austerity economics. Public services play an important role in tackling inequality, in part, as the OECD has observed, by mitigating the gross income inequality in the UK. We should recognise the value of proportionate universalism while targeting resources on preventative spending.

While centralisation is not the answer, that doesn't mean that in a small country there isn't a case for national frameworks. These could set out common standards, data sets and proportionate scrutiny. In particular, UNISON has long argued the case for a national workforce framework that would include common staff governance standards, training and start to break down the silos and make it easier for staff to move between services. I am personally increasing attracted to a longer term goal of the one public service worker with common terms and conditions, although I recognise that this has its challenges. Apart from facilitating integration, it would also reducing the significant costs associated with constantly reinventing the HR wheel.

Having national frameworks then enables greater localism, freeing up local democracy to focus on integrated service delivery rather than fragmenting services on the outsourced English model. This could be based around real communities; towns and discreet urban areas, with community hubs providing a base for most public service delivery. Services can then be designed with service users and staff, adopting system thinking principles, rather than the dead hand of the one size fits all approach.

Austerity may be the defining feature of public service delivery in Scotland, but we shouldn't let it define the sort of Scotland that we want. Public services play a central role in that vision and it is right that we take a considered look at how they are best delivered.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)